A FLEETING LANDSCAPE: RESURRECTING THE EDGES OF THE ESTUARY

Academic Project, Industrial Design Masters Thesis

Advisors: Ala Tannir, Charlie Cannon, Charlotte McCurdy, Mark Johnston, Shona Kitche, Tom Weis

Services: Industrial Design, Design Research; Climate & Sustainability

A Fleeting Landscape is a project based in Providence, Rhode Island that invites the city dweller to experience a mixed media microcosm of the marshes and discover what has been obscured through the encroachment of urban development. It is an invitation to look closely, find the connecting dots to the marshes, take a pause, and ground oneself in the environment that surrounds them.

Abstract

From the salt marshes of Rhode Island to their tropical counterpart in the Sundarban (pronounced: shundar-bon) mangroves of India, wetlands are the world’s natural barriers. Fighting against extreme weather events between land and sea, the edges of this fragile ecosystem continue to shrink and degrade as anthropogenic stressors (infrastructure development, unsustainable land use, and aquaculture) increase. In a 2022 report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) persuasively argues for the protection of wetlands as they are key ecosystems that help regulate temperature rise to 1.5º C. Despite the urgency, an appreciation for the wetlands exists at the periphery of attention.

Design

The experience is built through a combination of ephemera set to teleport the viewer to an alternate landscape in the salt marshes of Rhode Island. When immersed in this geo-psychological installation, the viewer reunites with nature, with a landscape lesser-known. They have an opportunity to engage deeply with the research and become agents of change towards the recognition and response of wetland ecosystems.

Download publication ︎︎︎

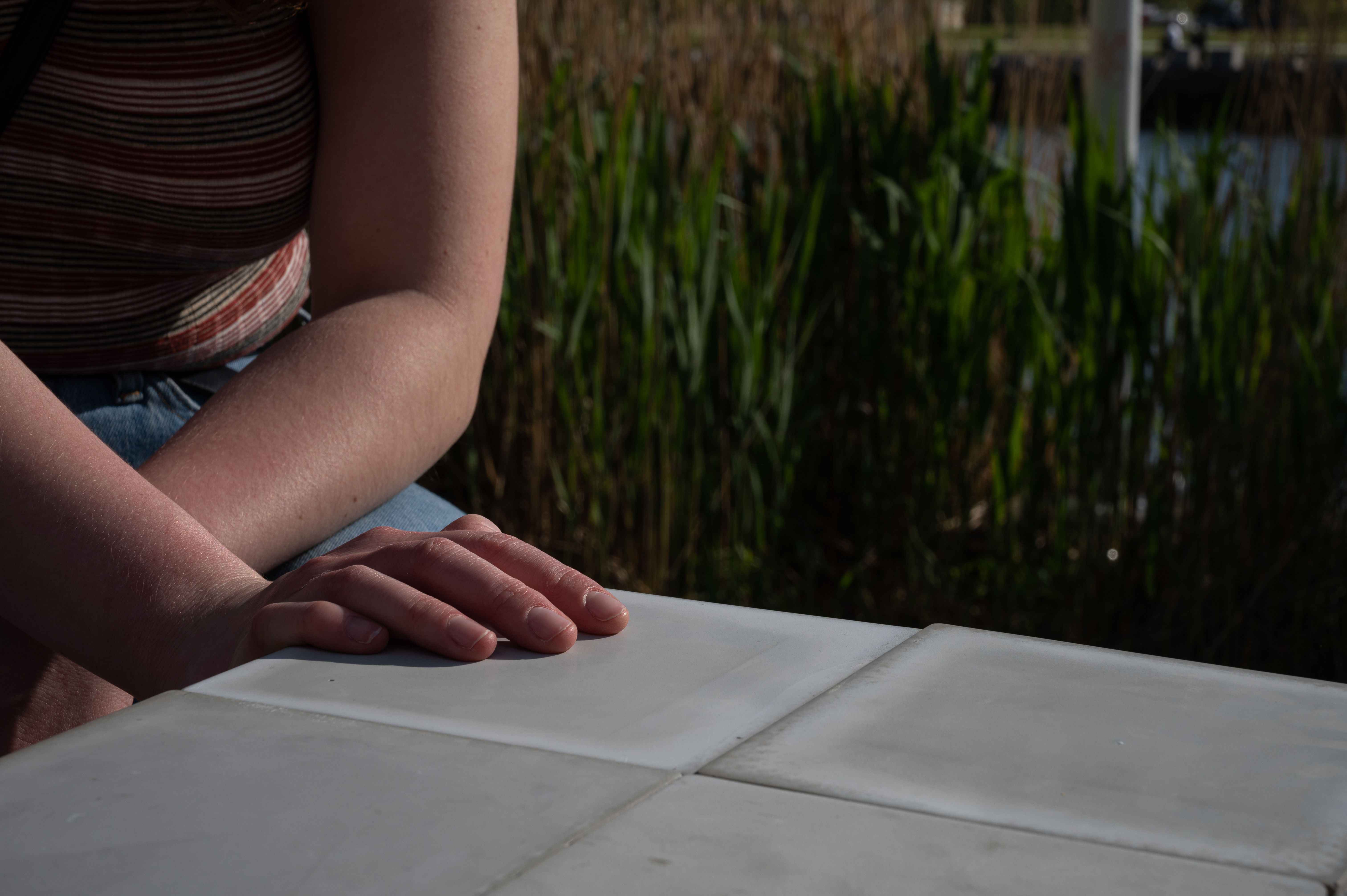

By embedding ecological curiosity* through objects in the public space the proposed design becomes a physical embodiment of historical and scientific research. The concrete tiles are symbolic of extractive interactions, layered atop the stratigraphic representation of a salt marsh.

Ecological Curiosity refers to an inclination or individuals’ drive to learn about local ecology and put the learnings into action through a community-powered response.

A square foot of the marsh was created using gravel, sand, and peat. It is adorned with native marsh grasses namely Spartina alterniflora and Distichilis spicata which were sourced locally and planted to represent a microenvironment.

Native marsh grasses, glass, sand, peat, hydraulic cement, plywood, ribbed mussel shells foraged from the marsh.